By Ramona Roberts

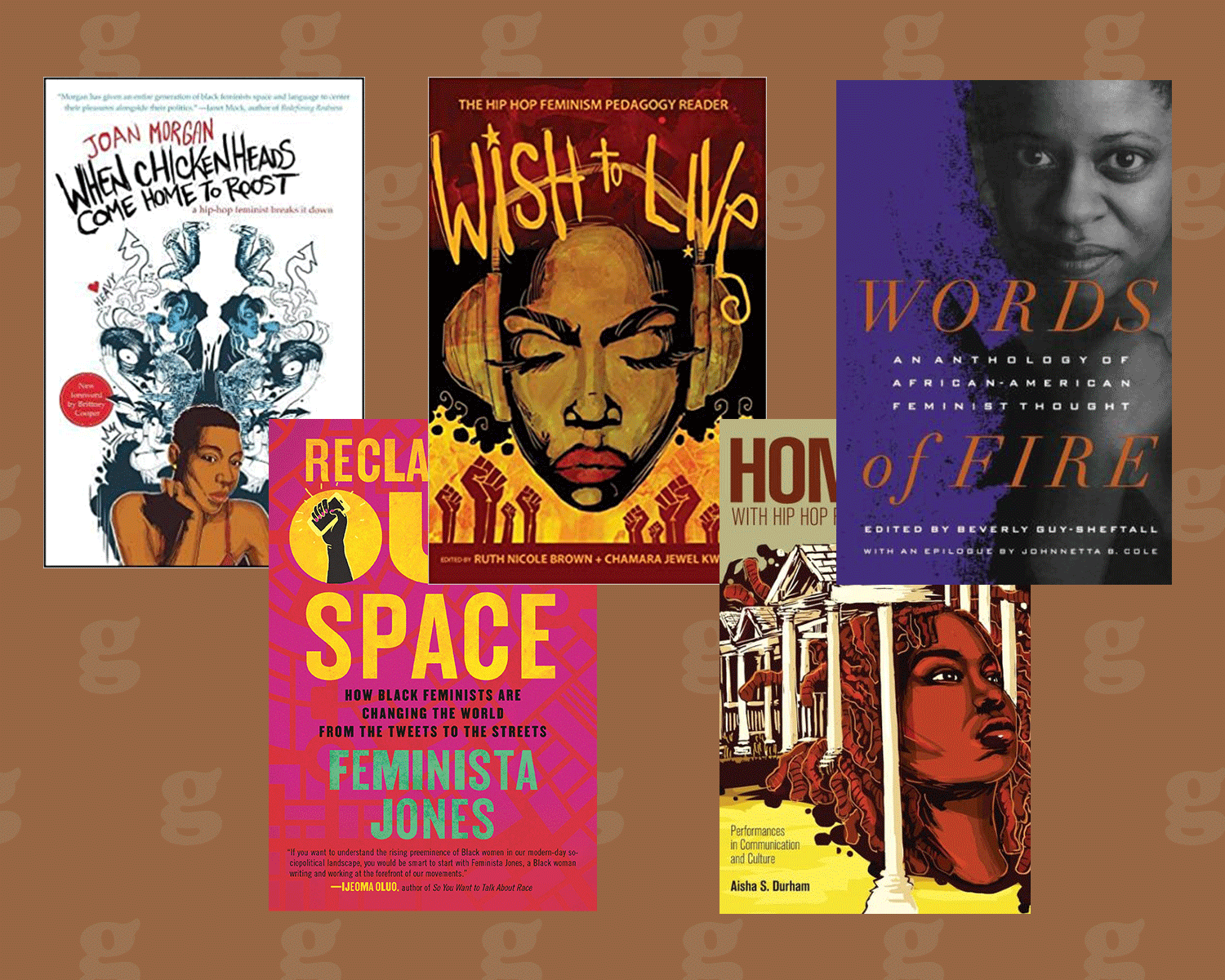

We know how impactful hip-hop music is. From lyrics to movies to film and fashion, hip-hop has played a major role in shaping the world’s culture. And when you consider the fact that Black women have been at the forefront when it comes to encouraging much-needed conversations on misogynoir, racism, and social change with society-at-large and within our own communities, it’s no surprise that some of the looks in hip-hop would become a direct reflection of these conversations.

When we talk about women's roles in hip-hop through the lens of fashion, the conversation often centers commercialized looks and our standard fan favorites. We have to be careful to include the full scope of history though, and recognize that there was an entire wave of women donning less commonly-worn styles and making their own rules in hip-hop fashion. This was displayed through women in the industry described in the 1980s as “conscious,” because their music and style was reflective of what has been deemed the politically charged sub-genre of Hip-Hop.

Queen Latifah, for example, reinforced the content of her music (and her rap name) with her fashions. Coming from the socially aware group Native Tongues, the queen MC complimented the political views in her music with her style. Through songs like “Ladies First” and “Fly Girl,” Latifah affirmed the power of women while rocking kente fabrics, African pendants, and embracing her name “Queen” with tall stylish crowns and kofias. During a 1989 episode of Yo! MTV Raps, she explained to Fab 5 Freddy, "By wearing African clothes, African accessories, not only am I supporting my African brothers and sisters who have these businesses, but it brings me closer to my ancestors...I just feel inner power." For Latifah, both her lyrics and her clothing made a political statement.

The same can be said of Ms. Lauryn Hill, whose style influenced many and reflected the conversations she had both in and outside of her music. In hip-hop feminist and scholar Joan Morgan’s She Begat This: 20 Years of the Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, Morgan notes the way Hill “signaled multiple spaces of Blackness in her style.” She sported locs and tams (crocheted hats usually worn by Rastafarians), and also challenged the notion of what she “should wear” by seamlessly shifting traditionally feminine looks and tomboy outfits. During an interview with Essence, Hill spoke on her relationship with fashion and the need to protect her “creative birthright” from exploitation. “Fashion is something I breathe, for example. It’s something I did very naturally, but I’ve seen my style, my look, everywhere. I wasn’t really trying to share my style, I was just trying to be me and exist.”

And from stylish head wraps and colorful long spaghetti strapped dresses to grillz and fedora hats, Erykah Badu’s fashion evolution has represented the themes in her music as well. In 2003 she released her third studio album ‘Worldwide Underground,’ incorporating hip-hop and funk elements into her neo-soul style to create a project that addressed racism, police violence, a man with a “complex occupation,” and more. At that year’s Essence Awards she rocked a lime green military-inspired suit, in line with the content on her album. In a 2020 interview with Essence, she spoke on the pressure of actualizing the perceptions that come with the box of neo-soul, even with her look. “As much as I appreciated it, it kind of made me feel trapped a little bit. I became the incense [and] candles poster child...[The headwraps] just got heavy, physically and a little bit mentally.” Today she continues to never limit herself with fashion and continues to steal the show with her bold style choices, such as her most recent 2021 Met gala look. "I have a good understanding of my own personal style...[I know] what looks good on my body, what colors look good on my skin. I'm not afraid to take risks. I mean, it's all creativity,” she shared during an interview with Instyle.

That’s just it, fashion is all about creativity and personal style. Clothes reflect who you are, what you think, the world around you, and the conversations you are having in it. Check out some of the looks we seldom discuss that we want to celebrate below!

Queen Latifah at the MTV Video Music Awards in Los Angeles, California. 1999.

Queen Latifah, circa 1990. Photo by Al Pereira/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Ms. Lauryn Hill on stage in New York City. 1999.

Ms. Lauryn Hill at the Billboard Music Awards. 1999.

Erykah Badu at the Academy Awards. 2000.

Erykah Badu at the Soul Train Awards. 2017.