by Amanda Wicks

Let my mama tell it, I was never going to “catch” a man. She thought I would grow out of my love for wearing oversized clothes and running with my older brothers as I transitioned into young adulthood, but I never did. My image didn’t mesh well with her idea of what a man wants but I had no desire to change. Not only did I abhor the idea of living my life just to appease the male gaze, but my mama was also loud and wrong.

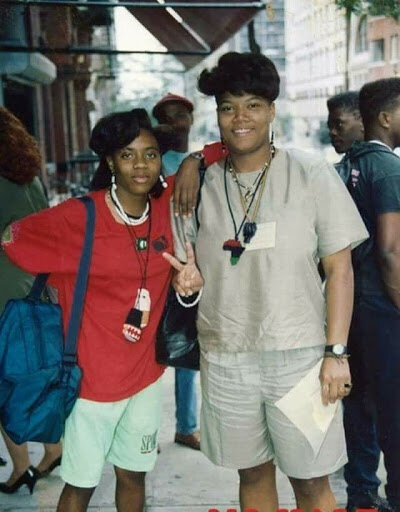

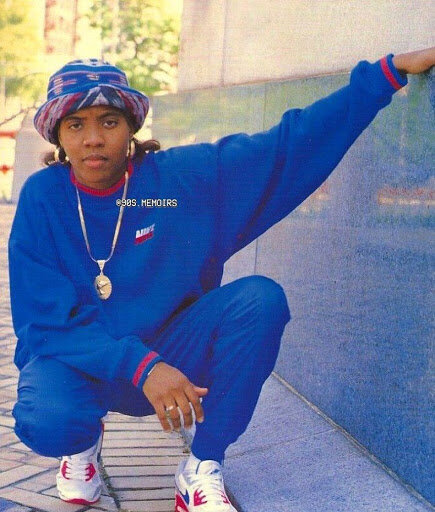

From Janelle Monae tippin’ on the tightrope in her well-tailored pant suits to Aaliyah being everybody’s 90s crush in her oversized Tommy Hilfiger gear, Black tomboys are gender-bending phenoms, defying the feminine-masculine binary. Though this seems normal in Hip-Hop culture, these women occupy a space that had to be carved by somebody, and one of the Black women who set the foundation for people like Missy Elliott, Queen Latifah, TLC, and MC Lyte is the force known as Stormé DeLarverie.

A quick Google search of DeLarverie will garner countless hits for articles, but they’ll most likely be about her notoriety as the spark that ignited the Stonewall Uprising, the catalyst for the gay rights movement in the United States. While this is a grand claim to fame, her impact on Black women and fashion is often overlooked because of it.

Born in 1920s New Orleans to a wealthy white father and a Black mother who was his servant, the soul of jazz was infused into DeLarverie’s life at a very young age. Her life centered a love for entertaining as she wowed crowds doing everything from riding horses for the Ringling Brothers Circus to touring with jazz bands. Even then, while she presented herself as stereotypically feminine, her deep baritone voice both captivated the audience and transcended their understanding of what a woman should be.

by Amanda Wicks

DeLarverie’s world shifted in 1995 when she made her way to New York City and joined the Jewel Box Revue, a female impersonator company,as the only woman and MC. She invigorated the historic Apollo Theater in Harlem night after night and helped cultivate a space where everyone, specifically the LGBTQ community, could be safe and free. The creators of the Jewel Box Revue actually prioritized hiring an all gay staff since the other revues of the time weren’t as “gay-friendly.” They were known for being no-nonsense about homophobia while touring, offering protection to those who simply wanted to enjoy the show. The world outside those doors showed no mercy, however, and DeLarverie had to grapple with that reality.

In her decision to become the first, and only, drag king in the company, DeLarverie was urged to reconsider. In an interview, she recounts this distinct moment in time when she says, “Somebody told me that I couldn’t do it, [be a drag king], and that I would completely ruin my reputation and that I had enough problems being Black. But I said I didn’t have any problem with it, everybody else did.” Despite pushback, she went on to do whatever the hell she wanted and became the star of the show.

Ironically, though, it wasn’t her masculine attire that garnered negative attention, it was her feminine street clothes. Between the 1940s and 60s, law enforcement drew upon legal codes against costumed dress, otherwise known as “masquerade laws,” to target the LGBTQ community, effectively arresting people for cross-dressing. Sexual deviancy and cross-dressing went hand-in-hand in the eyes of the law and the laws were their way of ridding the streets of “bad” people. DeLarverie was detained twice for dressing as a drag queen, so even when her garb “matched” her gender, she was seen as a threat to social normativity.

DeLarverie’s entire being represented a life suspended between masculine and feminine. Eventually, she became known for her butch attire. Well-tailored suits from London and men’s black leather jackets were her staples; still, however, the people closest to her asserted that DeLarverie maintained a stereotypically “womanly” presence. Her partner of many years, photographer Diane Arbus, captured one of the most well-known images of DeLarverie eloquently titled “The Lady Who Appears to be a Gentleman.” As noted in Arbus’ biography by Patricia Bosworth, Arbus once wrote, “[Stormé] has consciously experimented [with] her appearance as a man without ever tampering with her nature as a woman.” In this case, DeLarverie’s “womanly” nature was her inclination to help others. She was known by many as a caretaker of sorts, nurturing and protecting those around her.

Though one’s gender and sexual identity is often reduced to visible markers such as physical features and clothing, DeLarverie created a tension between perception and reality by tearing down the false dichotomy of masculine/feminine. Her suave yet tough exterior coupled with her gentle and loving nature subverted all understanding of what it means to be “ladylike.” DeLarverie’s unapologetic presentation of self is a manifestation of the Black feminist radical tradition that reimagines what resistance looks like. When tracing a history of rebellion, grand gestures are most applauded (I’m talking violently overthrowing slavery and leading a whole bus boycott), but it’s the resistance in the everyday that inches us closer to being able to live freely, especially for Black women.

DeLarverie chipped away at respectability and the patriarchal standards for Black womanhood simply by showing up and showing out in her menswear. Her attire didn’t render her less of a woman, instead, it accentuated her feminine prowess—turning heads with an ethereal beauty while exuding a depth and strength that nourishes and fortifies. On the shoulders of her resilience and courage stands a whole generation of Black women who aren’t afraid to be tomboys. Whether rocking a red lip and a tuxedo, or some lip gloss and baggy jeans, they defy societal norms and still manage to be the baddest. As written in a poem dedicated to DeLarverie, “Sometimes war paint is made by Maybelline, and sometimes the King is a woman.” Gender-bending women in Hip-Hop and beyond can stand a little more firmly in their true selves because King DeLarverie stood firmly in hers.